Looking Back

It all started when I visited the Social Services car park in 2004/5 and first conceived the idea that finding Richard’s grave was not only important but also a viable project. The visit changed my research focus from Richard’s life, to his death and burial.

It was the impetus for four more years of research, fitted in around an ongoing screenplay as well as the demands of single-parenthood with two teenage boys.

Because of the enduring interest in Richard III, there are prominent academics, scholars and researchers who have made King Richard’s life and times their specialty. Some are sympathetic to the king; some are not. There is also a Richard III Society (of which I am a member) dedicated to accumulating all the available knowledge and searching for more. So in the course of my work on a screenplay about Richard’s life, I was already at the leading edge of the latest Ricardian research.

The breakthrough was when I came across the work of Dr John Ashdown-Hill. In the summer of 2005, John announced what was for me his ground-breaking discovery of Richard’s mtDNA sequence. I now realised that we could potentially identify Richard’s remains if we found him.

I searched the Richard III Society’s archives. Contributors to its journals in the 1970s had discussed the present location of Richard’s grave in the now vanished Greyfriars Priory. They included the osteoarchaeologist Dr William White (Museum of London) and Oadby resident Audrey Strange. They both suggested the area occupied by three car parks to the south of the modern-day cathedral (St. Martin’s Church). Audrey had looked at the very widely believed story that Richard’s grave had been desecrated and his remains thrown into the river Soar. She put forward the compelling idea that it had become confused with that of John Wycliffe, the bible reformer, whose remains had been dug up, burnt, and thrown into the river Swift in nearby Lutterworth in 1428.

John also investigated the ‘bones in the river’ story which if true meant that a search for Richard would be pointless. So it was a big step forward when his research concluded that it had no reliable basis.

Then, in 2007, by a huge stroke of luck a small archaeological dig was underway in Grey Friars (street) when a 1950’s block of flats was being demolished. It was the location where two local researchers - David Baldwin and Ken Wright - had placed the church, and where a plaque had been erected. Nothing of significance was found. After consulting a number of old maps and texts, I reached the conclusion that they had placed the church too far east and the church and grave lay in the northern end of the Social Services car park. One of the people I contacted was Annette Carson, who was independently researching while living in South Africa. Her book Richard III: The Maligned King (2008) was the first I had read which, in addition to stating there was no reason to doubt Richard’s body still lay where it was first buried, also argued that this was probably ‘beneath the private car park of the Department of Social Services’– where our dig eventually took place.

It was in February 2009 that I took the momentous step of setting up a coherent project. I had invited John to give a series of talks to my branch of the Richard III Society, and at the lunch break when our research had dovetailed, and taking a deep breath, I announced the inauguration of the search for Richard’s grave. Under the title the Looking For Richard Project I put together a team which grew to include a distinguished list of experts in a variety of fields. Among its founder-members were historian Dr David Johnson and his artist wife, Wendy Johnson and, in 2011, on their returns to England, Dr John Ashdown-Hill and Annette Carson.

This was a unique project, and would mark the first-ever search for the grave of an anointed King of England. Never a trophy hunt, it was undertaken for neither gain nor glory, but as a respectful attempt to give honour to a king badly served by history. Its over-riding ethos was to retrieve the remains of Richard III and give them the respect and human dignity which had been denied when he was killed on the field of battle.

From 2009 there ensued 3½ years of effort. I had conceived of the search and gathered a team of Ricardian experts. Now I had to amass the evidence to convince potential partners that an excavation would be productive. These were years of pioneering research, planning and re-planning, investigations and radar surveys involving investments of time, effort and finance.

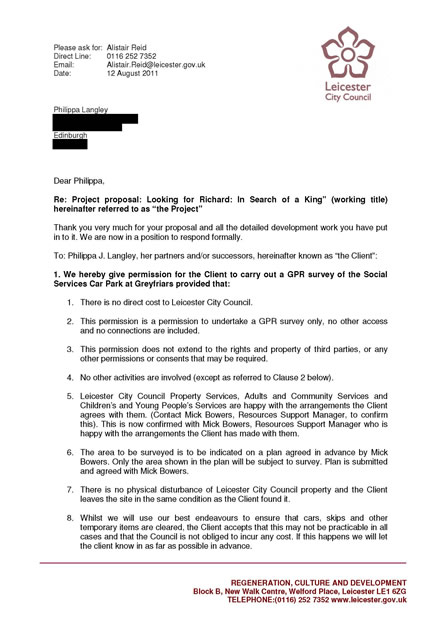

They were also years of writing, telephoning and knocking on doors, getting permissions from landowners, convincing the City Council to close a busy car park for 3 weeks, giving me as the client personal permission to dig, and to undertake my final research in the form of a Ground Penetrating Radar Survey by raising over £5,000 from Ricardians and private investors.

Then, with my plans approved, I had to raise money to commission a firm of archaeological contractors (ULAS). Our funds paid for the initial assessment, the dig, the costs of exhumation/s, the identification of one set of skeletal remains, and restitution of the tarmac afterwards.

As everyone now knows, our research proved accurate and we found Richard in the northern end of the Social Services car park, right where my research had concluded his grave would be, and where John had agreed was the likely location of the choir of the church. We call it a triumph for the open mind.

The Project had begun where the study of our past should always begin, with open minds and questions. We questioned the story of the 'bones in the river' and proved it false, dreamed up to suit a reputation people had been led to believe. I questioned that reputation, too, by commissioning the first Psychological Analysis of Richard III by two of the UK’s leading experts, accessible online here at http://www.richardiii.net/2_6_riii_psychological.php

By questioning, we are still bringing the historical Richard to light and disproving the myths surrounding him; myths that over time became ‘truths’. Years of work brought extraordinary results, demonstrating what can be achieved when preconceptions are set aside. In 2015 we commemorated finding Richard III – who knows what more is waiting to be discovered? My prediction is the study of late medieval history will never be the same again.

What Philippa Did

- Conceived the search for Richard III’s grave;

- Pinpointed the location of the grave and church as being in the northern end of the Social Services car park;

- Gathered the evidence that convinced her that an excavation would be productive;

- Spent years knocking on doors in Leicester trying to get permission for investigations, surveys and eventually a dig;

- Prepared a full plan for the project which was approved by the City Council (the landowner) and included a GPR survey, dig with DNA analysis, documentary film and reburial;

- Received further approval for the retrieval and reburial plan from the Ministry of Justice (Coroners and Burials Division), office of HM The Queen, Buckingham Palace, office of HRH The Duke of Gloucester, Kensington Palace, Royal Coroner, Lord Lieutenant of Leicestershire, Leicester Cathedral, University of Leicester and Mount St Bernard Abbey;

- Received personal permission as the client to undertake a GPR survey;

- Received personal permission as the client to undertake the dig and cut the tarmac;

- Received personal permission as the client for the filming of a TV documentary to record the retrieval and reburial project;

- Secured filming of TV documentary through UK production company;

- Pitched documentary as three-part series: Ep 1. Historical Richard III from contemporary sources from his lifetime; Ep 2. Search and archaeology; Ep 3. Identification (documentary became a single feature-length special). (Reburial documentary was not broadcast but in 2015 Channel 4 aired a three-part series of live events for the reburial: Return of the King; Burial of the King; The King Laid to Rest);

- Raised all the money to commission a GPR survey;

- Undertook an International Appeal that saved the dig from cancellation;

- Raised all of the money to commission the archaeological unit, cover costs of exhumation/s, including one skeleton identification, and restitution of the tarmac afterwards;

- Instructed exhumation of the remains in Trench One, agreeing a further payment of the remaining funding from the International Appeal;

- Commissioned the first-ever Psychological Profile of Richard III by two of the UK's leading experts.

The Return of the King

Looking For Richard was a unique project that marked the first-ever search for the grave of an anointed King of England. Never a trophy hunt, it was undertaken as a respectful attempt to give honour to a king who had been badly served by history. Its over-riding ethos was to retrieve the remains of Richard III and give them the respect and human dignity which had been denied when he was killed on the field of battle. In recognising the past we would not be repeating it, but making peace with it. There was nothing more powerful that we could do.

The news that Richard’s coffin would return to the battlefield as part of the re-interment had received a mixed reception but the team at Bosworth were clear. They would be honouring Richard by giving him what he didn’t get in 1485. As part of this, I had proposed the King’s Mounted Honour Guard, headed by Toby Capwell and Dominic Sewell, two leading 15th century specialists. This was approved immediately.

In Leicester it had been a tough two and a half years for the Looking For Richard Project to get my agreements honoured so that we could honour the last Plantagenet as we had envisioned and agreed from the start. The university had not ruled out putting Richard’s remains on public display and at first the cathedral stated it would not be giving the medieval king a tomb monument to mark his resting place. But as the time of the re-interment drew near and the king was coffined, not in a laboratory as others had proposed but in a former chapel with prayers, and laid out anatomically rather than as a pile of bones in an ossuary box, and with a new plinth with his name, motto and royal arms to adorn what would have been a featureless tomb, a sense of achievement and anticipation replaced that of earlier frustration and despair.

Sunday 22nd March dawned and the Gods were indeed shining down on us. Bright sunshine greeted the king’s coffin at the university as it appeared in public for the very first time and we placed our white roses on its sturdy English oak to honour him. No longer the scientific specimen and resource, King Richard was now the named individual. As I took my position at the back of the procession that walked behind his coffin towards the waiting hearse, I watched as the flags of the veterans lowered before it. They had come to honour Richard, the soldier and warrior king.

With the battlefield in Leicestershire wrestling with how to get me to their service at Fenn Lane, they had booked a taxi but the university now allowed me a spare seat in the second black limousine with the genetic relatives. This short journey behind the cortege was quiet; words meaningless and inappropriate as we each sensed the others quiet struggle with what we were undertaking – the final journey of the last Plantagenet.

The intimate service at Fenn Lane Farm honoured Richard in the location where it is believed he died. The three soils of his birth (Fotheringhay), life (Middleham Castle) and death (Fenn Lane Farm) were placed in an urn of the same oak as the coffin, made by Michael Ibsen. Here the battlefield gave me the honour of being the Custodian of the Soils. As the urn was blessed and I carried it to the waiting hearse, it marked a deeply moving experience for me as the writer who had led the seven and a half year search to find the king.

At Bosworth as the king’s coffin processed to the sundial, pulled by a troop of army cadets, the battlefield gave me a further honour of being the first to follow it. As I handed over my Custodianship of the Soil and the coffin received a twenty-one gun salute from all those at Bosworth, Richard’s namesake, and Patron of our Society, the Duke of Gloucester, lit a beacon in his name. Bosworth had indeed honoured its king

I’m often asked what moments stood out. There are so many but some I will carry with me for the rest of my life. On the Sunday, as I sat in the cathedral with a clear view of the south porch, I watched as outside Richard’s mounted Honour Guard, in the form of Toby and Dominic, rode to its doors and peeled off to stand guard for the king as his coffin entered. If ever there was a moment to be transported to Richard’s own time and see in action the ethos of the Looking For Richard Project in giving Richard what he didn’t get when he died on the field of battle, this was it. Another came at Fenn Lane Farm when, as Custodian of the Soils, the battlefield had awarded me the honour of carrying Richard’s life-story in my hands, and afterwards at Bosworth of being the first to walk behind his coffin. I cannot thank them enough for their kindness and generosity. And finally, my own personal moment of farewell at his tomb, arranged for me by the TV company Darlow Smithson, when I paid what private respects I could, and wished for Richard an eternal peace. But it was also at the re-interment with my ten year journey very nearly at an end. A poem by Carol Ann Duffy, the Poet Laureate, paid tribute to the king. ‘Richard’ captured the essence of the man and it seemed also the principles of the project to find and honour him in its profound and affecting verse.

The reburial of King Richard III was an unprecedented event, and historic journey. These are not easy to undertake but in the end everyone agreed that Leicester and Leicestershire had done the king proud. Richard had been laid to rest with all the dignity and honour that could be bestowed, and peace had been made with the past.

R Marks the Spot

This is from Philippa’s original website as she arrived in Leicester in August 2012 to undertake the first-ever search for the grave of an anointed King of England.

And yes, the letter R was the catalyst and driver for her 4 years of research and 3 and a half year battle to cut the tarmac in the northern end of the Social Services car park (as pictured).

Philippa’s research seemed to confirm that this could be the likely location of the lost priory church of the Greyfriars, but the only way to find out was to cut the tarmac and on 25 August 2012 – the anniversary of Richard’s burial in the Greyfriars in 1485 - a lower leg bone was uncovered.

Richard III was found beside the letter R, in the adjacent parking bay to the right. It was the first discovery of the dig, on the very first day.

At the dig, Langley discovered that the R had been painted onto the tarmac in the early 2000’s by Mike Mistray, the car park attendant, to denote a ‘reserved’ parking space.

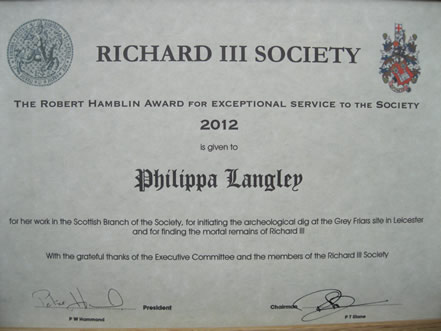

Robert Hamblin Award 2012

In October 2012, at the Society’s AGM in York, Philippa received the Robert Hamblin Award and Honorary Life Membership.

Robert Hamblin Award citation:

"The Robert Hamblin Award For Exceptional Service To The Society 2012 is given to Philippa Langley for her work in the Scottish Branch of the Society, for initiating the archaeological dig at the Grey Friars site in Leicester and for finding the mortal remains of Richard III. With grateful thanks of the Executive Committee and the members of the Richard III Society."

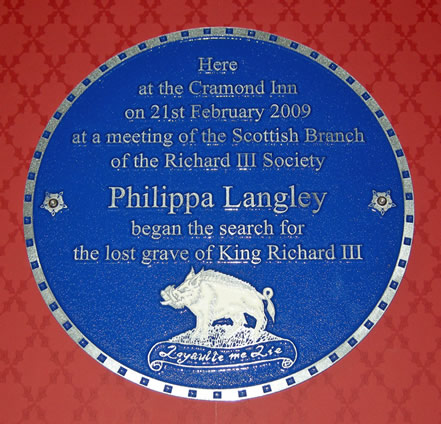

The Cramond Plaque

The Road to the Cramond Inn*

The Cramond Plaque is unique; it is the only plaque that commemorates the 2012 search for the lost grave of King Richard III. In April 2014, it was unveiled at the Cramond Inn, Edinburgh on the shores of the Firth of Forth.

*An excerpt from ‘The Cramond Plaque’ a Commemorative Booklet by Sandra Pendlington:

The 18th century Cramond Inn sits on the shore of the Firth of Forth in North West Edinburgh, close to where Edward IV’s fleet cut out eight ships of the Scottish Navy in 1481. It is the traditional meeting place of the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society and has become the surprising birthplace of the successful search for the lost grave of Richard III. This was commemorated on 12th April 2014 when Philippa Langley unveiled the Cramond Plaque at the Inn.

The road to the Cramond Inn began on 21st February 2009 at a Scottish Branch study day organised by Philippa, the branch secretary, who had invited John Ashdown-Hill to give a series of talks. When John and Philippa finally met in Edinburgh he agreed that Philippa’s working hypothesis was possible – the church of the Greyfriars, where Richard had been buried in 1485, must be situated in the northern end of the Social Services car park.

So the Looking for Richard Project began on the shore of the Firth of Forth at the Cramond Inn, Edinburgh. The story moved away from Cramond to Leicester and on 25th August 2012 Philippa and the project team achieved their objective – Richard III had been found. The following March the Scottish Branch held their AGM at the Cramond Inn. Under any other business the minutes recorded the following:

‘That the Branch would present the Cramond Inn with a discrete wall Plaque to commemorate the fact that the decision to launch the successful search for King Richard’s body at Leicester was taken there – it being appropriate to permanently mark the place where the adventure began.’

12th April 2014 was a bright sunny day with a strong wind whipping up the waves on the Firth of Forth. The Inn had reserved the room where the Plaque was covered. After lunch Philippa got up to speak. She spoke of the search, the support of fellow Ricardians in the Scottish Branch and said that ‘it wasn’t until I saw the Plaque yesterday that I finally realised that we had found Richard’. She then turned and pulled the cord and the covering fell away to cheers from the members. The Plaque is a simple blue roundel with the words picked out in silver.

‘Here at the Cramond Inn on 21st February 2009 at a meeting of the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society Philippa Langley began the search for the lost grave of King Richard III’

It includes a white boar above Richard’s motto and two roses, one on either side of Philippa’s name.

Looking back we all felt the emotion of that day. Pride that our secretary had achieved something that was said to be impossible, delight at being there on such an auspicious day and privilege at taking part in the event.

As we left to journey home, we left behind the first memorial commemorating the successful search for King Richard, and the only portrait of King Richard in Scotland.

For an update about the Cramond plaque, please see News page: 6 April 2019.

Richard

by Dame Carol Ann Duffy

The Poet Laureate’s eulogy, written for Richard III’s re-interment on 26 March 2015, was read by Benedict Cumberbatch and dedicated that evening to Philippa Langley by Leicester Cathedral who commissioned it. It was perhaps an olive branch at the end of a gruelling two year battle fought behind the scenes with the cathedral and university authorities to see the medieval king honoured in the way that had been planned and agreed from the start. On Saturday 22 August 2015, at the 530th anniversary of the Battle of Bosworth, Philippa read the poem at the service of remembrance to all those fallen in battle.

Richard

My bones, scripted in light, upon cold soil,

a human braille. My skull, scarred by a crown,

emptied of history. Describe my soul

as incense, votive, vanishing; your own

the same. Grant me the carving of my name.

These relics, bless. Imagine you re-tie

a broken string and on it thread a cross,

the symbol severed from me when I died.

The end of time – an unknown, unfelt loss –

unless the Resurrection of the Dead...

or I once dreamed of this, your future breath

in prayer for me, lost long, forever found;

or sensed you from the backstage of my death,

as kings glimpse shadows on a battleground.

Philippa's Research

As part of the 2022 ten-year anniversary of the discovery of Richard III on 25 August 2012, Philippa has published her research work. Her papers cover a period of seven years from 2004/5 to 2011. We hope you enjoy seeing Philippa’s journey that got her to the northern end of the Social Services car park in Leicester where the king was found. This takes Philippa's journey to her final research with the Ground Penetrating Radar survey on 28 August 2011 prior to the dig getting underway.

Philippa's research was first published in 2014 in Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project. For more information, please see here.

Philippa will publish more research papers and documents shortly.

Philippa's Journey:

2004-5_1. Audrey Strange (1975)_Richard III Society

2004-5_2. Rhoda Edwards (1975)_Richard III Society

2004-5_3. Carol Simmonds (2003)_Richard III Society

2005_4a. David Baldwin (2002) Church in Grey Friars (street)_Leicester Mercury (Oct 2002)

2005_4b. Ken Wright Plan (2002) Church in Grey Friars (street)

2005_5. Stephen Butt (2004) Leicester Chronicler_Richard III Foundation

2005_6. John Ashdown-Hill (Oct 2005)_Time Team Letter

2007_7a. Ken Wright (Jul-Sept 2007) Grey Friars (street) dig

2007_7b. Langley (2011) Grey Friars (street) dig location

2007_7c. Langley (2011) Grey Friars (street) plaque (1990)

2007-8_8a. David Treybig Research (1999)_Geoff Wheeler, Richard III Society

2007-8_8b. David Treybig Research + Maps (1999)_Geoff Wheeler, Richard III Society

2007-8_8c. David Treybig Research (2000)_Geoff Wheeler, Richard III Society

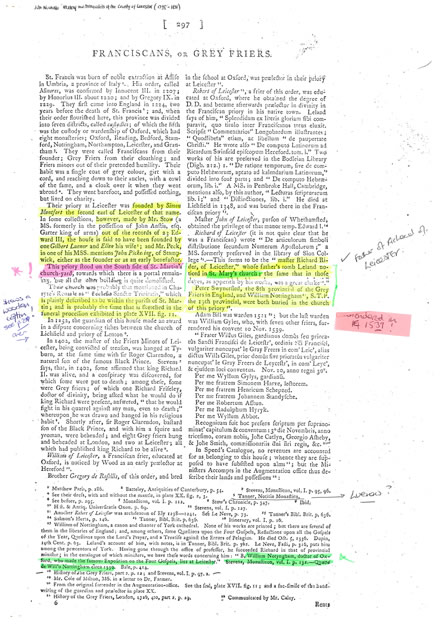

2007-8_9. John Nichols (1795-1815)_Geoff Wheeler Copy, Richard III Society

2007-8_10. Maps (1975-2003) enlarged_Geoff Wheeler, Richard III Society

2007-8_11. John Throsby (1792) map

2007-8_12. C J Billson (1920) 2 pages_sender not recorded

2008_13. Chris Wardle (Jun 2008)_Richard III Society

2008_14. Lorraine Pickering (2003)_Medelai Gazette, Richard III Foundation

2008_15. John Nichols (1815)_National Library of Scotland

2008_16. John Throsby (1792)_National Library of Scotland

2008_17. Annette Carson_ Maligned King (2008)

2009_18. John Ashdown-Hill (Feb 2009)_Honour My Bones_Richard III Society

2011_19. C J Billson (1920)_National Library of Scotland (Jan 2011)

2011_20. Mathew Morris & Richard Buckley, Visions of Ancient Leicester (Jul 2011)_ULAS

2011_21a. Annette Carson (Aug 2011)_Maligned King_message

2011_21b. Annette Carson_Maligned King_front cover

Philippa's Agreements

To commemorate the tenth anniversary in 2022 of the discovery of Richard III on 25 August 2012, Philippa has published the agreements which preceded the commencement of her archaeological search. Philippa applied for, and was granted, three permissions by the landowner, Leicester City Council. These included authorization to commission and fund a 2-week dig (plus 1-week of restitution work). The king’s remains were uncovered on day 1 of the dig and exhumed on day 12, in the precise location identified by Philippa’s research (and intuition). As the project’s client, Philippa also instructed exhumation of the remains (at the northern end of the Social Services car park) with the last of the funding raised by her International Appeal to the members of the Richard III Society. This eleventh-hour intervention not only averted cancellation of Philippa's 2-week dig, but also established the Society members as her principal funding body, providing 53% of the required finance.

Philippa's story is fully documented in The Lost King: The Search for Richard III (first published as The King's Grave: The Search for Richard III, 2013) and in Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project, 2014. Her instruction to exhume the remains in Trench One is recorded in both accounts (p.100 & p.54 respectively). In 2014 Philippa was informed by Leicester City Council that her story in the soon to be opened Richard III Visitor Centre had been rewritten by Leicester University. This was undertaken without her knowledge or consent. As a result, Philippa had no alternative but to seek legal representation. Immediately prior to the king’s reinterment week in March 2015, Philippa’s story was reinstated. This included her instruction for exhumation and payment of the last of her funding from the Ricardian International Appeal.

1. ULAS AGREEMENT_1_15 MARCH 2011

2. LEICESTER CITY COUNCIL AGREEMENT_01 JUNE 2011 UPDATED 12 AUGUST 2011

3a. ULAS AGREEMENT_2_11-177WSIGreyfriarsV(4)_JUNE 2011 FOR 2012 DIG

3b. ULAS AGREEMENT_2_11-177WSIGreyfriarsV_5_UPDATED FOR EXHUMATION 3 SEPT 2012

As the recognised client, Philippa entered into all of her agreements in Leicester in good faith.

Her agreements have have also been published in Finding Richard III: The Official Account, see: Bookshelf.

Financing the Dig

As the 25th August 2022 marks the tenth anniversary of the discovery of Richard III, Philippa has published a breakdown of the financial contributions raised to pay for the archaeological search which discovered the king. As the project’s client (see Agreements above), Philippa was responsible for securing the funding that enabled the 2-week dig (with one week restitution work) to go ahead. The landowner, Leicester City Council, Philippa’s Lead Partner in the search for Richard III, underwrote the 2-week dig with a £5,000 contingency budget (please see below):

Funding (in order of contribution):

Richard III Society and members17,367(52.84%)*

Leicester University10,000(30.43%)

Leicestershire Promotions Ltd5,000(15.21%)

Leicester Adult Schools500(1.52%)

Total:£32,867(100%)**

*Plus a further payment to ULAS of £716 to cover costs including exhumation of Richard III’s mortal remains (total: £18,083)

**Leicester City Council - £5,000 contingency

Following the discovery and exhumation of the king (which took place on day 1 and 12 respectively, as above), the dig was extended into a third week, utilising the city council’s £5,000 contingency budget. Leicester University then stepped in to underwrite the third week of digging work. Following discovery the university funded post excavation costs, including the scientific identification of King Richard’s remains. For Philippa’s pre-dig commissions and funding (Desk-Based Assessment, £1,140; Ground Penetrating Radar Survey, £5,043), see Finding Richard III: The Official Account (2014), pp.44, 46-48, 52.

Leicestershire Promotions was the first party to 100% finance Philippa’s 2-week dig. When this funding was withdrawn, the first person to make a financial contribution to the project was Dr Phil Stone, former Chairman of the Richard III Society. Phil generously donated £5,000 of his own money. For more on the project and its funding, see above and here. For Philippa’s receipts, see here. For original costings see here. Costings would eventually be reduced to £32,867 following minor adjustment of trenches to allow for additional parking and removal of coffin and pall costs.

The university’s costs can be viewed here. Please note: the university conflates all costings and is incorrect in its assertion that they were the first to contribute funding and underwrite the dig project that discovered the king.

Dr John Ashdown-Hill self-funded his research and discovery of King Richard’s mtDNA sequence (published 2005). This original research work amounted to over £3,000.

For full funding including Langley’s costs from 2010-12 (comprising research and development, travel, accommodation, rights and permissions) see FAQs here.

Procession

Philippa was not invited to walk behind King Richard’s coffin for the official procession in Leicester. This honour was awarded to Sir Peter Soulsby, Dr Richard Buckley and Fr Stephen Foster.

A Statement from Philippa

“Contrary to the misleading media statement issued by the University, I did feel side-lined (and continue to feel side-lined) by the University wrongly taking my credit for leading the search for the King’s remains. The only press conference that mattered was the one on 4 February 2013 to confirm that the remains were those of Richard III. That conference was the one attended by the world’s media. I was not invited by the University to sit on the panel that faced the journalists and the University wrongly presented themselves as leading the search that I had commissioned and paid for. It is true the University invited me to address the conference but as the 13th of 13 speakers, long after the live TV news feed had ended.

As for the general whereabouts of the extensive Greyfriars precinct - where some (not all) believed Richard III might be buried – yes this was known, but no one knew the layout of the buildings and therefore where the Greyfriars Church itself (and therefore the body of the King) might be (if he wasn’t in the River Soar as most leading historians then believed). Only through my intuition and research was the precise area identified where the dig should take place. In a matter of hours of starting to dig, the King’s remains were revealed. If the University (and everyone else) knew exactly where to dig, why hadn’t they done so before?”

You can discover more about Philippa’s incredible story and 8-year journey to find the king in: The Lost King: The Search for Richard III (2013) and Finding Richard III: The Official Account of Research by the Retrieval and Reburial Project (2014). See here

First Public Announcement

On 1 October 2011, the first public announcement concerning the search for the King’s grave in Leicester was made. This was by the Richard III Society. At its AGM in London, Executive Committee member Richard Van Allen reported that the project was “led by a Society member” and centred on “a council car park near the cathedral”. Ground Penetrating Radar “had produced positive results and it was hoped that a television documentary would be made”. The announcement was later published in the Ricardian Bulletin magazine on 1 December 2011 (p.4), as part of the AGM Minutes, see here.

Getting Underway

On 14 July 2012, a few weeks prior to the dig and search for the king getting underway in the Social Services car park, it was the intention for Leicester City Council, as Philippa's Lead Partner and landowner, to manage the communications for the project. Sarah Levitt, (see below), alerted Leicester City Council's press team to the successes in Philippa's (second) fundraising appeal and explained by email: “I have copied in Philippa Langley who is leading on this project so you can ask her for more details if needed.”

On 1 March 2013, the Ricardian Bulletin recorded the following from Sarah Levitt, Philippa's Lead Partner at Leicester City Council, and landowner in the search for the King's grave: "In March 2011 I was asked to attend a high level meeting in the council. Philippa had not dealt with a council or commissioned an excavation before, and what she was suggesting was a tall order, since the [Social Services] car park was heavily used for essential council business and it was hard to see where the money could come from. Nevertheless, she made a good case and as a result I was asked to be the lead council contact.

And so we set out on our long journey. There were many setbacks, which Philippa unfailingly approached with charm, commonsense, a willingness to learn, relentless determination, and a spirit of co-operation, all of which encouraged people along the way to share her enthusiasm and want to be involved.”

“Finally Leicester City Council would like to thank one extraordinary lady, Philippa Langley, who followed her dream and never gave up. She was a joy to work with and the good she has done for the people of Leicester, as well as for the world's understanding of King Richard III, can never be underestimated.”

Sarah Levitt, Head of Arts and Museums, Leicester City Council.

Memorandum of Understanding

Memorandum of Agreement regarding the use of images of King Richard’s remains - 28 September 2016

A Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) agreement with the University of Leicester regarding the appropriate use of the images of King Richard’s remains has been obtained. This came about because of the concern expressed following the discovery of a University tee shirt with a photograph of the king’s skull and, following this, the graphic artwork by Alexander de Cadenet, using a radiograph, or x-ray image, of the same.

Following a meeting with the University on 29th July to discuss the use of images, Philippa and I are pleased to announce that the MoU between our two organisations has now been signed and is published here. Publication of the agreement is so that all observers, as well as those who supported Philippa’s Looking For Richard Project with funding and everyone who bought into the ‘dignity and honour’ ethos that governed our whole project, can see that not only do we have this agreement in perpetuity, but that nothing is hidden.

You will see that the University maintains its right to use the images of the king’s remains for the purposes of ‘research, education, learning and teaching’. It also maintains its right as the copyright holder of the images to have the final say on any future use. The agreement does not stop the University from allowing the use of images but if they dishonour the spirit of the agreement in the future, the Society, and the public, will be able to hold them to account for it.

In securing this agreement, Philippa has fought a long battle, with my full support, to achieve this result. It is a great achievement and we believe, moreover, a moral victory. The University’s stance had been that Philippa had no agreements or understandings with them but Point 9 of the MoU now reflects the actual position for the first time. Philippa has confirmed that the signing of the agreement marks the end for her of a long and difficult journey in Leicester to honour Richard in the way that had been planned and agreed from the start. In seeing the Society’s signature in perpetuity upon the agreement, she is now able to draw a line in the sand. She is, as she put it,‘finally free’.

Dr Phil Stone (1946-2020)

Chairman

Richard III Society

Read the Memorandum of Understanding

You can also view the Statement and Memorandum of Understanding here on the home page of the Richard III Society.

Scottish Branch

You can read more about the history of the Looking For Richard Project with the Scottish Branch of the Richard III Society here.

All images © Colin G. Brooks, Philippa J Langley, Annette Carson, University of Leicester, Leicestershire County Council, Darlow Smithson Productions, Lost in Castles, Looking For Richard Project.